Stirling Castle

|

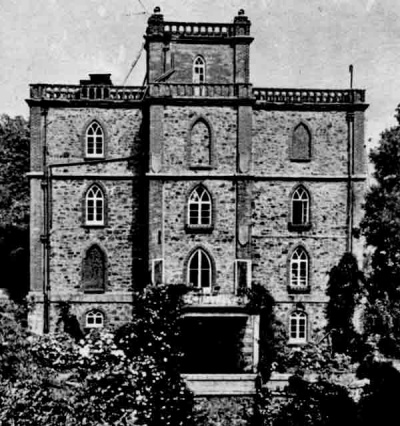

Stirling Castle on Mont Neron in Grands Vaux has been described by one author as "quite the strangest house to be found in Jersey" (Campbell, 1967) and by a guide book as "a Victorian monstrosity". However, until recently the history of this house and the unusual biography of its builder has been shrouded in mystery. As a result of several years research, many curious and interesting facts about the Castle and its founder, Edward Stirling, have now come to light.

Romantic legend

The history of Stirling Castle has been somewhat confused by a certain amount of romantic legend associated with the Napoleonic Wars and a certain Captain Charles Stirling RN, who, it is claimed, built the castle to act as a signalling station prior to the construction of Fort Regent (Campbell, 1967). A close inspection of the Registry of Contracts in St Helier, however, shows that there was no such building on the site during the first two decades of the 19th century. In fact, the site was acquired by Edward Hamilton Stirling from 1847 to 1848 in an undeveloped state. The corner stone of the Castle was laid in June 1850.

The owner of the land, Edward Stirling, was a retired civil servant of the East India Company who, after years of ill health and failing eyesight, had retired to the island. It was as a result of research into Stirling's unusual and interesting Indian career, and enquiries which were made for his missing journals and papers, that the details of the founding of Stirling Castle and Stirling's tragic personal life after his retirement were revealed.

Edward Hamilton Stirling was born in 1797, the eighth son of Andrew Stirling of Drumpellier, now a part of the town of Coatbridge, a few miles east of Glasgow. This branch of the Stirling family of Scotland was extremely well connected and was one of the foremost mercantile families in Glasgow, having considerable trading interests in Virginia and India. Two of Edward Stirling's relatives receive a mention in the Dictionary of National Biography. His maternal uncle, Admiral Sir Charles Stirling (1760-1833), served in the West Indies until his disgrace in 1810 after being convicted of "corrupt practices" and placed on half pay. Edward's older brother, the fifth son of Andrew Stirling, became Admiral Sir James Stirling (1791-1865), the first Governor of Perth colony, Western Australia [1829-1839].

Adventures

Edward Stirling's own career in the Indian Civil Service began in 1813 when he entered Haileybury College and received high recommendations in several subjects. In July 1817 Stirling took up his first post as Assistant to the Collector of Taxes in Agra (Bengal Presidency) and rose in the usual way through the ranks until he became Collector of Taxes in his own right. At this point Stirling's unassuming career was interrupted by his decision to take leave of absence, and travel through Persia, Afghanistan and back to India. At the time this was one of the most dangerous and pioneering journeys anyone could undertake. Only a very few individuals had managed to reach India by this route; and that only after innumerable hardships and dangers. Others had already perished in the attempt.

Stirling left Bombay on 9 February 1828 for the Persian Gulf and began to record his impressions in a journal which he maintained throughout his travels. The details of his eventful and historic journey to Tehran, and on to Mashhad, the Uzbek Khanates, or principalities, of what is now northern Afghanistan, Bamiyan and Kabul, have lain unread for the last 150 years and only now are the surviving volumes of Stirling's journal being published. There is insufficient space in an article of this length to go into detail about Stirling's historic journey, and it is sufficient to say that his travels from Mashhad to Kabul broke new ground in the European exploration of Central Asia.

He became the first European to visit the upper reaches of the Murghab river and to see the important Uzbek towns of Maimana and Sar-i Pul. He was the first European explorer of his generation to return alive from northern Afghanistan or, as it was then known, Turkistan. Only Moorcroft and Trebeck in 1825 had preceded Stirling and they had both perished from disease or, possibly, poison.

Return to India

After innumerable adventures, including travelling in disguise for part of the journey, Stirling returned to India in April 1829, having overstayed his leave of absence by about three weeks. Despite having informed the Government in Calcutta that he had been unavoidably detained and having had reassurances from the British Ambassador in Tehran that the results of his investigations would be of great use to the Government, worried as it was by threats of a Russian invasion of Persia or Afghanistan, Stirling found that his post had been filled and he was placed on half-pay.

He complained bitterly to Calcutta about this unfair treatment, made a claim for reimbursement of his expenses and offered to make available the results of his explorations to the appropriate government department. Not only was his request for reinstatement turned down, but his assertion that the Government should pay his expenses was bluntly and rudely rejected. It was not until 18months later that finally Stirling was given a posting that was of equal standing to the one he had lost. It would appear that, in the light of Calcutta's rejection of his claims, Stirling did not forward to the Government any substantial amount of information about his journey.

Stirling Castle

From 1830 to 1846 Stirling managed to pick up the pieces of his career and rose through the ranks of the Civil Service without particularly distinguishing himself. This may have been due, in part, to failing eyesight, which eventually forced him to resign the service. He arrived in Jersey in 1846 and began to acquire property in St Helier. In October 1846 he purchased a house on the north side of Vauxhall, and over the next two years acquired the land on which Stirling Castle now stands, as well as other properties in the town. No plans of the original Stirling Castle have been found, but the Jersey Times, on 7 June 1850, records the Masonic ceremony which marked the laying of the foundation stone.

Other newspapers report that the building was to be in the Asiatic style, with cupolas, etc. However, the final building shows no trace of cupolas or the Asiatic style. The only remotely Asiatic feature of the house is the Masonic temple, and its symbolic stained glass motif, which Stirling had had incorporated into the design of his Castle. Why the style of the building differed from that which was originally planned is just one more mystery surrounding the enigmatic life of Stirling.

While Stirling's new home was under construction, another of his properties, near the Castle, attracted the attention of the Jersey Agricultural Society who, in June 1850, went on a tour of the farms around St Helier and "first proceeded to the farm of Mr Edward Stirling ... where they found good rising crops of carrots and parsnips, also good crops of winter tares and beans".

Marriage

It was an event later in the year, however, that was to plunge Stirling into further confusion, bitterness and disappointment. It is not clear when, or how, Stirling first met the young and ambitious Anna Isabella Glascock, but she may have been visiting relatives in the island. We do know, however, that on 21 September 1850, she and the now blind Edward Stirling were married in St Helier, by special licence, before the Rev Doctor James Booth. Stirling at the time was 53, his wife merely 23. Given the events that followed so quickly after their wedding, it is likely that the penurious Anna Isabella saw in Stirling a rich and rather gullible person whose quick demise would leave her a widow of considerable means.

It was not long after their marriage that Mrs Stirling's true character was revealed. On 16 October, just over three weeks after the wedding, Anna announced to her husband that she was leaving and returning to London. This was done against the express wishes of Edward, and with a show of great impatience and irritation on her part. Fifteen days later she returned, accompanied by the Rev Doctor Irvine and her mother who, between them, appeared to have patched up the quarrel for a couple of weeks until, on 15 November, the Stirlings left for St Malo on a belated honeymoon; presumably in an attempt to repair a relationship which was on the verge of breakdown.

The couple boarded the South-Western but Edward soon discovered that an acquaintance of his wife, a certain Captain Benjamin Page, Aide de Camp to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, was aboard also. He was attached to the British Embassy in Russia and was en route to Paris with despatches. On their arrival in St Malo, the Stirlings booked into L'Hotel de France, along with Captain Page, who insisted on having the room next door to the Stirling suite. Page also dined with the couple. During the meal Page sat next to Mrs Stirling, and they both took advantage of Edward's blindness to conduct themselves in a most improper and indecent manner, passing notes and openly demonstrating their affection for each other.

That night Mrs Stirling was seen leaving her suite and later coming out of Page's room. Meanwhile Stirling, suspecting something was afoot, groped his way down the corridor in search of his faithless wife. The following day Stirling turned his back on his wife and left, without her, for St Helier. Page and Mrs Stirling, meanwhile, went to Paris and thence to London, taking lodgings in Dulwich. Mrs Stirling took with her jewelry to the value of £800, presumably a wedding present from her husband.

Brother's death

During the early part of December, Edward Stirling, still recovering from the shock of the last three months, was saddened further by the death of his eldest brother, William. News of this death had also reached his wife, who initially thought that it was Edward who had died. On 31 December, Stirling received a long and maudlin letter from his "affectionate wife" apologising for her conduct and explaining that, as Captain Page was like a close relative to her family, her conduct with him was justifiable. She informed her "Dear Edward" that she was seriously ill, in deep financial trouble and, unless he sent her funds immediately, she would be thrown into the street. She claimed that it was not just herself she was anxious about, but also the safety and security of 'his' child. No further reference is made to this child either in the ensuing court proceedings or in Stirling's will and one assumes, given Mrs Stirling's history of unfaithfulness, that the child's father (if indeed there was a child) could have been one of several men.

Probably Stirling never bothered to reply to his wife's letter, which was in thoroughly bad taste. If he required further proof of his wife's insincerity and audacity, Stirling soon had it. In mid-January 1851 Stirling received a letter from Captain Page himself, which had been forwarded to him by a certain Mr Evans of Jersey. In it, Page had the audacity to demand that Stirling pay bills to the value £150, the costs incurred by Mrs Stirling during her travels with Page. Included in the expenses were costs for medicines, indicating that Mrs Stirling's claim to have been ill had some foundation.

By the time Stirling received this letter, Anna Isabella was back in Jersey. The reason for her return is not clear, unless it was a rather naive attempt to effect some sort of reconciliation. This seems unlikely, however, given her conduct during her residence in the island. From 6 to 8 January 1851 she lodged at the York Hotel, and then moved to furnished rooms (un hotel gami) at 22 Belmont Road, where she stayed until the 13th. Whilst in these lodgings, she struck up various liaisons, conduct which probably made it desirable for her to quit these rooms after only a few days and move to the Bath Hotel in Mulcaster Street, where she stayed until 15 January. Once more she made the place too hot to hold her. The proprietor's wife complained to her husband about Mrs Stirling's visitors, and he ordered her to leave the Hotel.

Since the divorce proceedings do not mention her moving to another house in Jersey, we assume that Mrs Stirling left the island. We are not told whether she made any attempt to meet her husband. News of his wife's arrival, and the scandals which followed her everywhere she stayed in St Helier, may have forced Edward Stirling to institute formal proceedings for a divorce, a mensa et thoro, in the Jersey Ecclesiastical Court, on the grounds of proven adultery. Since Jersey at the time had no civil divorce, this was Stirling's only hope of a legal annulment of his marriage. Presumably Mrs Stirling was well aware of Jersey's lack of divorce laws when she married him in the island, and realised that there was little hope of her husband ever being able to effect a legal dissolution of their marriage.

Divorce hearings

The case of the Stirlings' divorce became an immediate society scandal in the island, with the local newspapers publishing the detailed articles of divorce in full. The Impartial gave nearly three columns of its middle pages to the petition and published all the names of the individuals indicted for adultery or criminal immorality with Mrs Stirling. It emerged that Mrs Stirling, even before her marriage, had been far from a model of chastity, allegedly having had an affair with the Rev James Booth, the very minister who had married the Stirlings. Mrs Stirling, however, was not present to answer the charges, and all efforts by the Court officials to trace her had proved unsuccessful. The Court ordered a notice of the charges to be posted at her last place of residence and, in the event of her failing to answer the summons of the Court, proceedings would be continued as if she were present.

The court did not reconvene until June 1851, by which time matters had become even more complicated. Mrs Stirling had filed her own case against her husband in a London Court, claiming an allowance as his wife. The Court dismissed her application and ordered her to apply for this through the Jersey Courts, which she did later in the year. At the next session, in October, her claim was discussed. By this time the main legal argument of the divorce had shifted from the actual petition for divorce to Mrs Stirling's claim for alimony.

This raised interesting legal points for the lawyers representing both parties and the issue of Mrs Stirling's infidelity became marginalised. It was not until May 1852 - over a year after Stirling had initiated the proceedings - that Mrs Stirling finally put in the personal appearance that the Court had demanded. This seems to have been the last time she ever visited the island and the legal matters were, from that time on, handled by her solicitor.

The arguments over the rights, or otherwise, of an estranged wife to demand maintenance from her husband during divorce proceedings, which he had initiated against her, continued. Stirling was obliged to produce a statement of his fortune, which showed he was worth in excess of £31,000 a year, though Mrs Stirling's lawyer claimed that he was worth nearly twice as much. The details of Stirling's fortune were published by the press and, presumably, read by the local criminal fraternity. In November 1851 Stirling's unoccupied house in Le Grand Val was broken into and stripped of the greater part of its contents. In February 1853, the same house was burgled once more with similar results.

The Court proceedings ground on with little hope of the case ever being settled. Some token swearing in of witnesses took place in December 1851, and Mrs Seward, the landlady of the Bath Hotel, began her testimony. By May 1852 the local newspapers had lost all interest in L'Affaire de Madame Stirling, partly because some of the sessions were held behind closed doors and partly because there was now little prospect of further revelations about Mrs Stirling's affairs.

In the latter part of 1852 Stirling was obliged to go to Paris to attend the funeral of an unnamed uncle, and while in France he fell ill, thereby delaying the legal proceedings even further. Finally, in July 1853, the Court accepted Stirling's own assessment of his income but took a further eleven months before deciding that Edward Stirling was legally obliged to pay his wife maintenance, which was awarded at £100 a year. Thus, ironically, Stirling was obliged to bear the costs of his wife's defence as well as his own.

Wife's death

Sometime towards the end of 1855 Mrs Stirling fell seriously ill somewhere in the north of England and Edward again appeared before the Court to complain that, since she had once more failed to appear to answer the charges against her, he had no legal obligation to continue to support her. By now newspaper reports showed considerable irritation at the way in which the proceeding had dragged on, designating it L'interminable proces Stirling-Glascock. Despite this criticism, the case continued unresolved until the untimely death of Anna Isabella in the first half of 1859.

Thus, after eight years of unresolved legal wrangle, Stirling was freed finally from this disastrous, scandalous and costly marriage which had caused him so much acute public embarrassment and private distress.

Barbie Mertz

Meanwhile the blind Stirling had to make arrangements for the supervision of his household affairs in the absence of a wife. He had planned the ground floor of Stirling Castle without the inconvenience of doors, substituting wide arches instead, to afford him the best possible mobility. Then, possibly before his wife's death, Stirling engaged a certain Barbie Mertz, known locally as Miss Mars. Little is known of this woman, though, if the entry in the 1861 census can be trusted, she was born around 1826. She was much younger than her employer, who was greatly indebted to her and left all the contents of the Castle to her in his will. In 1863 he also gave her two houses in St Helier; 31 Clarendon Road and 2 Tudor Place.

The nature of the relationship between Edward Stirling and Miss Mertz may have been merely that of master and servant, but there are some slight indications that the relationship may have been closer. Firstly, there is the generosity of the will. In addition to a bequest of his personal possessions - including some valuable silver and oriental antiquities - Stirling had previously given her two well-appointed houses. Furthermore, included among the occupants of Mont Neron in the 1861 census is a seven-year-old girl named as Anna Sophia Nertz (Mertz?) who is stated to be a "friend" of Barbie Mertz. The name indicates that this child was related in some unknown way to Miss Mertz and possibly to Edward Stirling. The child died in August, 1864, and nothing further is known about her or her parentage.

Stirling's final years passed quietly and little is known of the last decade of his life. Given the trouble and scandal that had accompanied his move to Jersey he was probably glad to live out his last years in relative obscurity. Finally he passed away on 14 December 1873, at the Castle, and was buried in Mont à l'Abbé Cemetery by the north wall- a site only recently opened and affordable only by the cream of Jersey society. His funeral appears to have been well attended, given the number of pairs of gloves that the undertakers charged to Stirling's executors.

Among the mourners was Charles Stirling, his nephew, who inherited the Castle and the other properties that his uncle had not already bequeathed to Miss Mertz. Since Charles Stirling was living in Tunbridge Wells at the time, he put his uncle's Jersey property up for sale. Miss Mertz also auctioned the contents of the house. Having completed the sale of Stirling Castle, Charles Stirling returned to his modest house in Upper Grosvenor Road, Tunbridge Wells. However, the new wealth he had acquired from his uncle's estate led him to move house, possibly to a better area of the town.

Amongst the personal effects bequeathed to Miss Mertz were, probably, personal papers and the Journals of Stirling's travels in Central Asia. In addition to the item listed as '12 Journals' in his will, there was also an album and notebooks. It may be that these 12 journals, of which only five volumes have survived in the archives of the Royal Geographical Society in London, were the complete account of Stirling's remarkable journey in 1828-29. It is something of a mystery how these volumes reached the Society's library, and the missing volumes remain to be discovered. The Stirling Journals, as they stand, are incomplete.

Epitaph

Stirling's epitaph, regrettably, makes no mention of his historic journey and, apart from the coat of arms of the Stirling family, the pink and white marble edifice is far less imposing than many of the other late Victorian tombs and monuments in Mont à l'Abbé cemetery. Though in need of some repair, the inscription remains clearly visible:

MEMORY OF

EDWARD H STIRLING Esq.

LATE OF THE HON EAST INDIA

COMPANY'S CIVIL SERVICE

YOUNGEST SON OF THE LATE

ANDREW STIRLING Esq.

OF DRUMPELLIER, NEAR GLASGOW.

HE DIED IN THIS ISLAND

ON THE 14th DECEMBER 1873

AGED 76 YEARS.

Stirling's life was one marred by misfortune and is surrounded by an aura of sadness and mystery. The failure to gain proper recognition for his pioneering travels while in India meant that he returned to the relative obscurity of the Indian Civil Service, while others, most notably Alexander 'Bukhara' Burnes, were able to claim, unjustifiably, the fame due to the earlier generation of pioneering Central Asian travellers, Moorcroft and Stirling. The loss of his eyesight was a further sorrow and one which forced him to curtail his career in India. Even during his enforced retirement, Stirling was dogged by misfortune and tragedy with his marriage and subsequent divorce proceedings, the robbery of his house, etc. His blindness also removed him from other public functions and he was forced to resign as the treasurer of the Royal Sussex Masonic Lodge, of which he had been a founder member. The imminent publication of the extant parts of Stirling's travels in Central Asia and of this article will, it is hoped, do something to redress this lack of recognition.